A Successful "Snipe Hunt"

By Dan Weisz

|

| All photos by Dan Weisz |

The old practical joke of sending someone on a "snipe hunt" began in the mid 1800s and has continued through the years. The idea was to send a friend on a fool's errand at night, hunting a mysterious and non-existent creature called a snipe. Well, Wilson's Snipes are real, shorebirds widespread throughout much of North America. They arrive in Tucson every winter but are hard to find due to their color, their habitat, and their secretive nature. I found a few Wilson's Snipes late in December at Sweetwater Wetlands. The harsh mid-day lighting made it tough for me to get good photos, but I do like this shot of a resting bird, its long beak tucked in on its back.

Thanks to this year's successful burn to clear vegetation from Sweetwater, there is much more exposed water and mud flats than usual. As a result, this winter's snipe population is much easier to find. I returned to Sweetwater last week and found quite a few fairly easily. If the Snipes aren't on a mudflat, they can be found in nearby shallow water, searching for food with their very long bill.

The Wilson's Snipe probes the mud for food with its long bill. It is looking for insect larvae and other invertebrates. The tips of the bill are both sensitive and flexible, so when the snipe finds food, it is capable of opening the tips of its bill without having to open its entire bill.

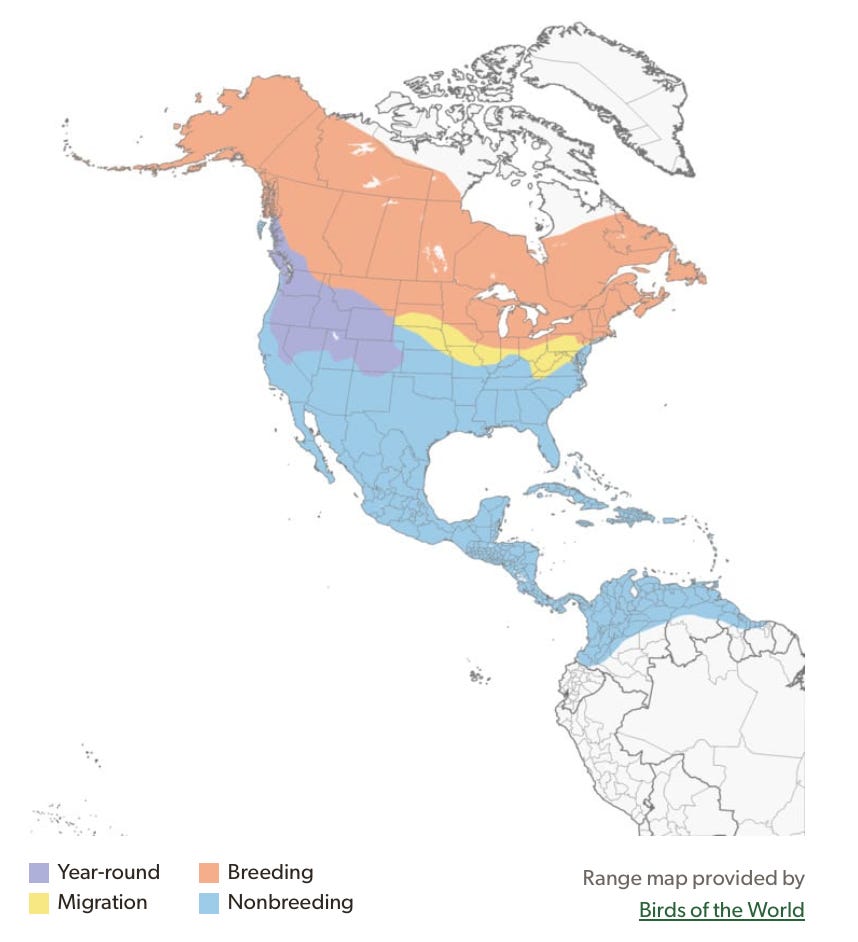

The range map shows how widely the Wilson's Snipe disperses throughout the Americas during winter (the blue area).

At rest, the Wilson's Snipe remains alert and has its lengthy bill tucked into its back feathers.

Hunting again, the snipe walks through shallow water, waiting to use its long bill to probe the mud for food. The bill is about four times as long as the Snipe's head is wide.

Again, the snipe reaches through the water and into the ground in search of food.

Wilson's Snipe often walk along the edge of the pond or the mud flat in search of food. Here, you can see the double reeds behind the Snipe. Moments earlier the Snipe was on the other side of those two reeds hunting. The head of the Snipe has three white lines across its head and matching stripes down its back.

You can see how deeply into the mud it can probe with its beak. The bill is covered with mud. When probing for food, the tip of the snipe's bill is flexible and can open and manipulate food while the base of the bill remains closed.

Changing behavior, the Snipe probes straight out rather than straight down. Like other birds, it is adapted to be successful in its environment. Snipes can slurp food into their mouths while probing the mud.

The word snipe may come from its long beak. The Old English "snite" and the Middle English "snype" are related to the word for snout.

Another fun fact from Wikipedia: “The name sniper comes from the verb to snipe, which originated in the 1770s among soldiers in British India in reference to shooting snipes, a wader that was considered an extremely challenging game bird for hunters due to its alertness, camouflaging color, and erratic flight behavior. Snipe hunters therefore needed to be stealthy in addition to being good trackers and marksmen.”

The snipe is referred to in Shakespeare's Othello. Read more about it.

If you do want to go on a successful “snipe hunt,” now is the time to head out to Sweetwater Wetlands. Good luck!

Dan Weisz is a native Tucsonan and retired educator who enjoys birding, being in nature, and taking photographs.

Comments

Post a Comment

Thanks, we value your opinions! Your comment will be reviewed before being published.